A practical guide to the product operating model

There’s growing interest in product operating models, and for good reason. When done well, they create clarity, speed, and impact. According to McKinsey, companies with more mature product operating models see 60% higher total returns to shareholders and 16% higher operating margins than those in the bottom half.

But most teams and organisations are still only scratching the surface. And the moment you try to go deeper, you're met with frameworks, tooling, and transformations that promise a lot but often deliver more noise than progress.

We wrote this article to offer a clearer, more grounded view. Not a manifesto. Not a methodology. Just a practical, working definition of what a product operating model means to us, and what it looks like in action.

If you’re already moving towards a product operating model, try our free, confidential health check. It shows how you’re performing across culture, strategy, discovery, delivery, and teams, and gives you clear next steps.

So, what is a product operating model?

It isn’t a playbook.

It isn’t an org restructure.

It’s a shared understanding of how your product engineering function and the wider organisation work together to create and grow great products - what you believe, how you work, and how decisions get made.

In practical terms, a product operating model covers:

- How you set up your product engineering capability, and wider organisation - the roles, teams, and lines of communication

- How you work together - in teams, across teams, across the wider org, from exec down to individual contributors (ICs) and back up again

- How you choose where to focus your time and energy

And it ladders up nicely to Hyperact’s five core beliefs which underpin our approach to product development more broadly:

- Continuous discovery & delivery – discovery is not a one-time phase but an ongoing practice embedded into everyday work.

- Product engineering – the best product teams don't separate "what to build" from "how to build." Engineers, designers, and PMs co-own solutions from the start.

- Fast, incremental value – thin, vertical slices of value should be shipped continuously, validated in production, and iterated based on feedback.

- Flow over governance – minimise handoffs and approvals; empower teams with a clear direction and a set of guardrails.

- Evidence, not opinions – use data, user research, and real-world experimentation to drive decisions, not HiPPOs (Highest Paid Person's Opinions).

What does a product operating model look like to Hyperact?

A strong product operating model doesn’t happen by accident. It’s the result of deliberate choices about structure, roles, ways of working, communication, and strategy — all pulling in the same direction. What follows is a practical view of how we think about these foundations, shaped by what we’ve seen work across different teams and stages of growth.

Product function

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer to how you should structure your product function, but there are patterns. Most organisations tend to follow a fairly predictable journey as they grow — in size, in product complexity, and in maturity of their product development practices.

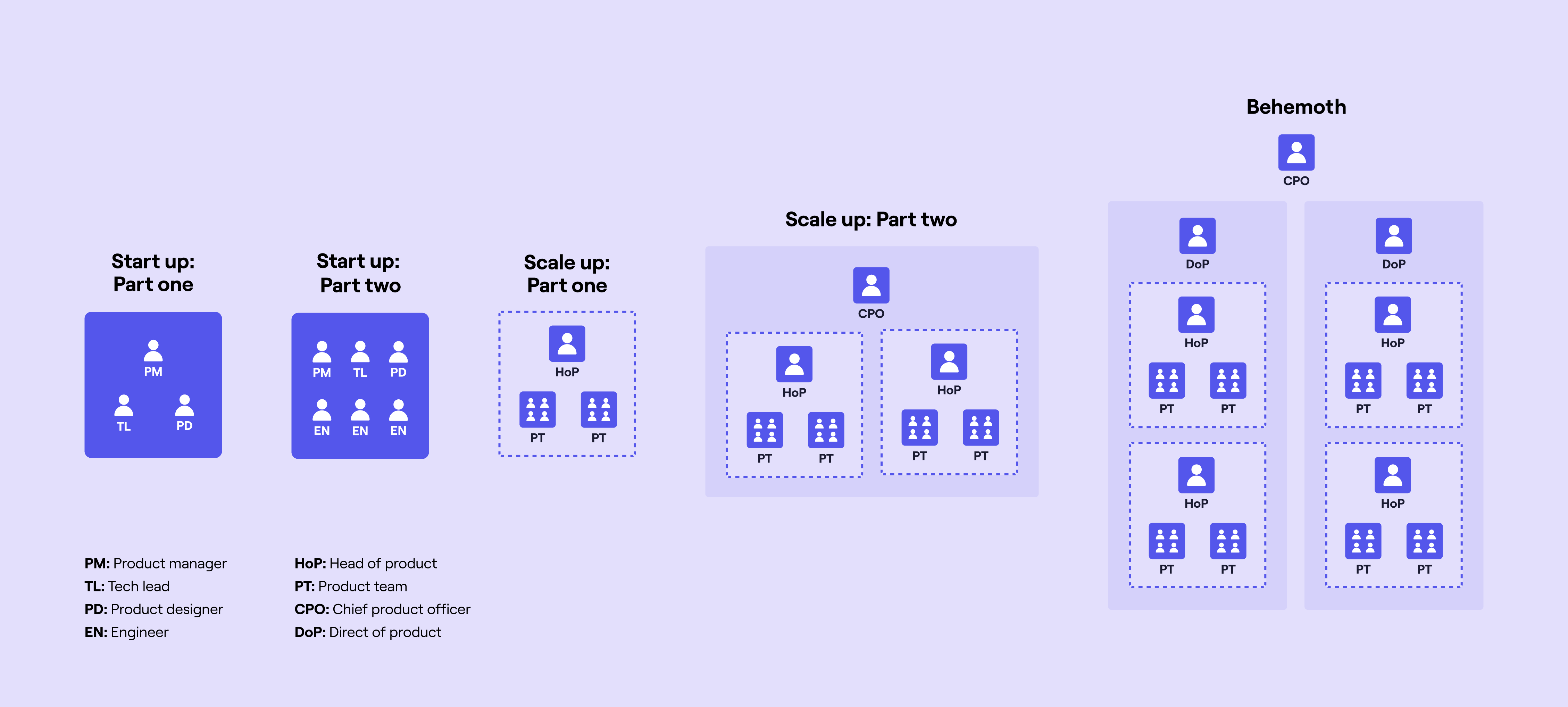

At Hyperact, we group these into five broad stages:

🐣 Start-up: part one

🐥 Start-up: part two

🧑🏫 Scale-up: part one

🧑🎓 Scale-up: part two

🐉 Behemoth

You don’t need to fixate on the exact category you fall into. The point is: as you grow, alignment starts to fray. Communication overheads increase. Decision-making slows. And the systems, rituals, and roles that once worked just fine start to break.

That’s when structure matters. But structure should serve your teams - not the other way around.

We’ve captured one view of how your product function might evolve in the illustration below.

It’s not gospel. It’s a starter-for-ten. Use it as a provocation, not a prescription.

The goal here isn’t to slavishly copy the structure of your favourite product org. It’s to consciously shape your own based on where you are now, and where you’re trying to get to.

Product teams

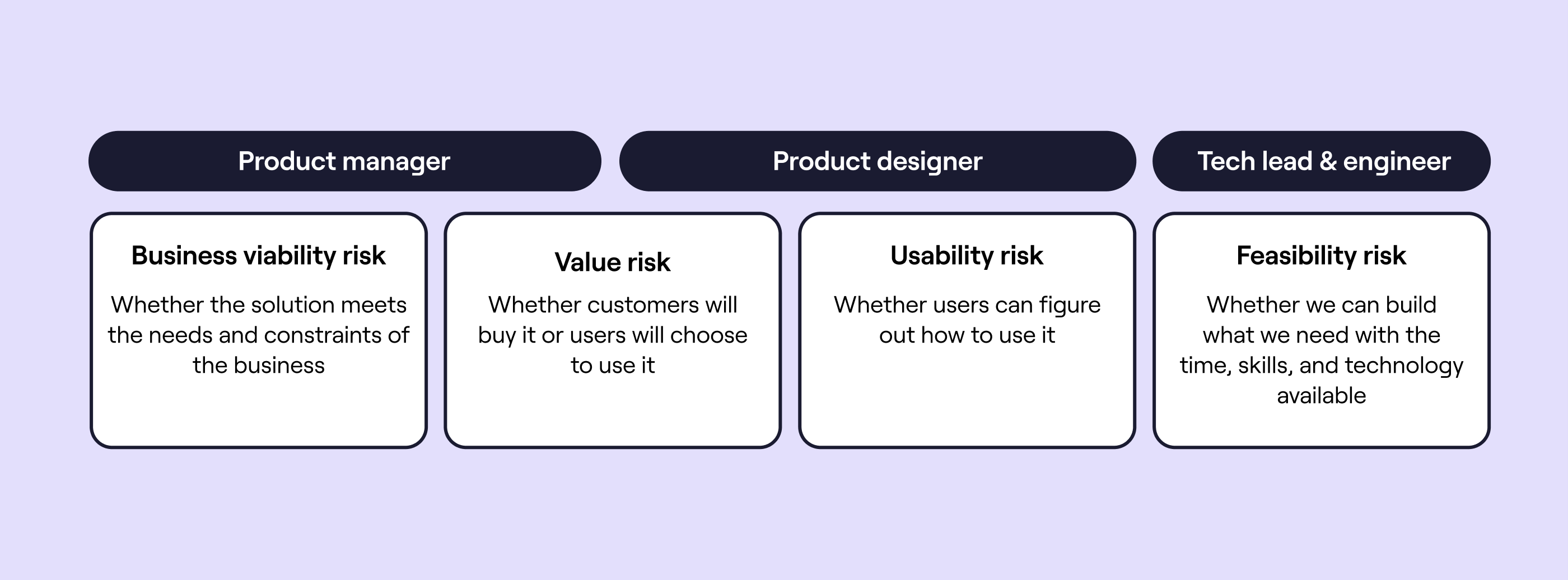

When we build product teams at Hyperact, this is the shape we aim for. It’s balanced, proven, and gives the team everything they need to go from insight to outcome with minimal friction:

- 1 × Product manager - owns value risk and business viability. They make sure the team is solving real problems in a way that works for both the customer and the business.

- 1 × Product designer - tackles usability and value. They shape the experience, make sure it’s clear and compelling, and lead the team’s design and discovery efforts.

- 1 × Tech lead - manages feasibility risk. They guide the technical approach, support the engineers, and ensure the solution is scalable and maintainable.

- 4 × Engineers - build the product. Ideally with a full-stack mindset and a strong sense of ownership. Fewer handoffs, more momentum.

We’ve used this structure time and again across different organisations and stages of growth. It works - not because it’s perfect, but because it brings together the core capabilities needed to consistently ship meaningful value.

This isn’t theory — it’s a starting point we’ve seen work in the real world. From here, you can layer in additional roles based on the shape of the problem and the maturity of your org. But if you’re looking to build a strong, empowered product team, this is a solid place to begin.

You can dig deeper into the thinking behind each of these roles in our core roles article.

Modern product engineering ways of working

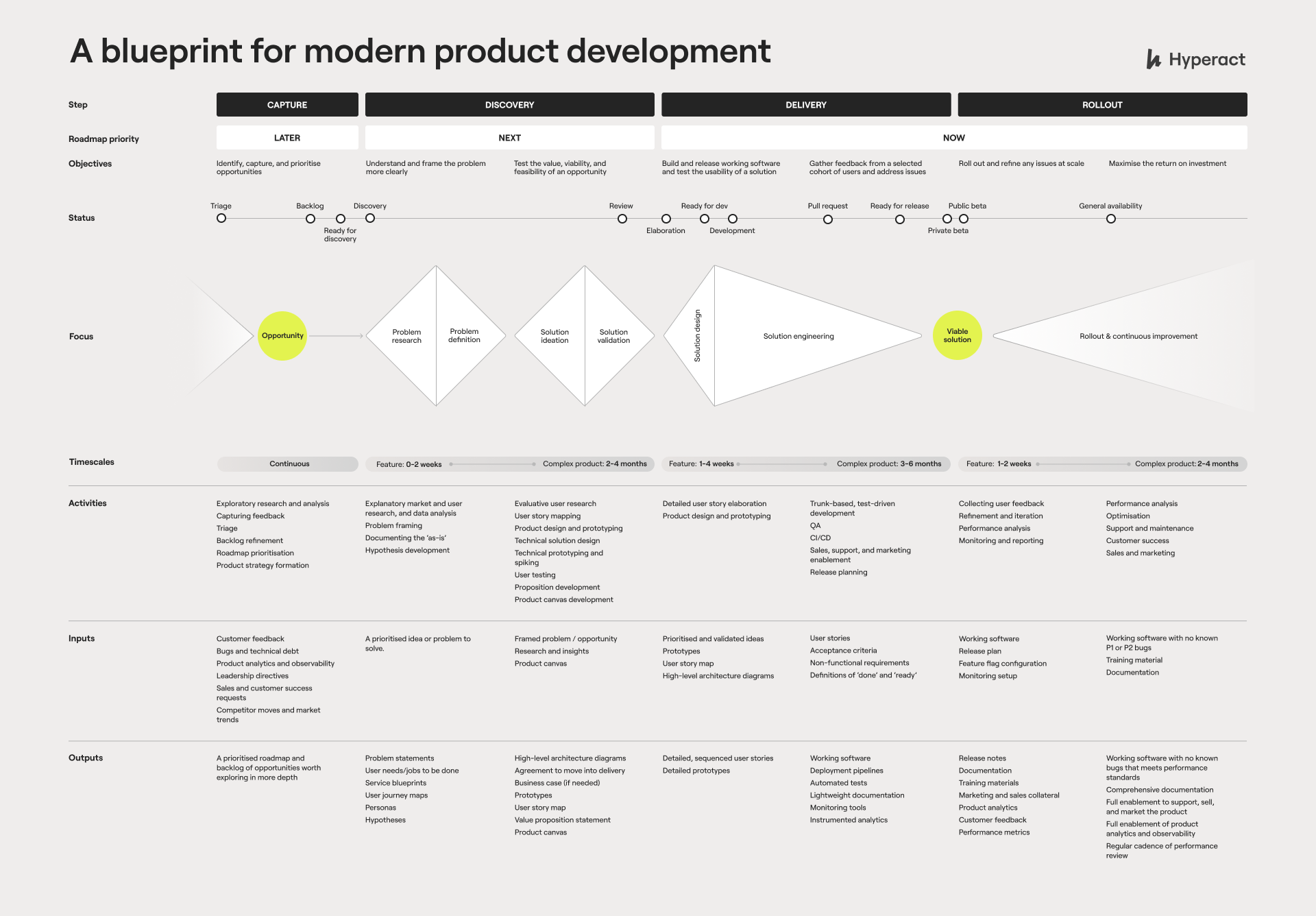

The best product teams don’t follow a rigid, stage-gated process — they work in loops. Ideas come in, value gets shaped, tested, built, released, and improved. And that loop runs continuously.

At Hyperact, we think of modern product development as a series of connected activities that help reduce risk, speed up feedback, and increase the likelihood that you’ll actually solve the right problem:

1. Capture

You need a clear, deliberate “front door” for opportunities — ideas, feedback, bugs, insight from data, commercial pressure. If you’re not careful, this turns into a mess of Slack messages, support tickets, roadmap spreadsheets and exec asks. Done well, it’s a filter, not a funnel, helping teams focus on what matters.

2. Discovery

This is where you explore the opportunity. Understand the problem, test possible solutions, validate assumptions. Crucially: you don’t need to get to perfect. You just need to be confident enough to move forward. Discovery doesn’t end here — it runs alongside delivery too.

3. Delivery

Build working software in thin, vertical slices. Focus on value. Keep work in progress low. Test early and often. Full-stack/product-minded engineers reduce handoffs and keep the loop tight. Quality is everyone’s job.

4. Rollout

Ship small. Ship safely. Use feature flags, observability tooling, cohort tracking, and clear success metrics. And keep listening — real users using real features in the real world will always reveal something you missed.

Each stage is tightly coupled with the others — you’re always feeding back, refining, and adapting. The stronger your loop, the stronger your product capability. And the stronger your ability to learn. Healthy product orgs don’t just ship — they treat feedback (from customers, data, and each other) as fuel. Every loop is a chance to listen, improve, and close the gap between what was intended and what was experienced.

You can read more about the detail in our product development blueprint, but if your teams are struggling to deliver, struggling to learn, or just struggling to move — this is where we’d start.

Org-wide collaboration and comms

In a healthy product organisation, communication isn’t a layer on top — it’s embedded in how teams work, make decisions, and connect with the rest of the org.

This isn’t just about the product teams. It’s about how product, engineering, design, commercial, operations, compliance — all the parts of the organisation — stay connected without grinding each other down with meetings and approvals.

Here’s what that can look like in practice:

- Every team has a clear identity and surface area

The organisation knows what each team is for, what they’re working on, and how to engage with them. Team canvases or Team APIs may help here — not as a form to fill in and forget, but as a living description of purpose, scope, responsibilities, principles, and cadences. It helps neighbouring teams, execs, and new joiners orient quickly.

- End-to-end journeys are mapped, shared, and revisited

Service blueprints and story maps are part of the operating rhythm — not just one-off workshops. They help teams work across functions and spot gaps between what’s designed, what’s delivered, and what actually happens. They also give commercial, ops, and support teams a seat at the table early, not after the fact.

- Connecting product with the business

Product doesn't sit in a bubble. In strong orgs, product strategy and roadmaps are shaped with input from sales, support, marketing, and finance — not just “shared” with them after the fact. The best teams act as connectors, not gatekeepers. This can be particularly crucial around launch events.

- Work is visible across functions

People don’t need to chase down decks or ask around for updates. Work in progress is clearly visualised — whether that’s delivery boards, upcoming initiatives, or rolling roadmaps. It’s easy for teams to see how their work interacts with others’, and for leaders to understand where energy is going.

- Communication is lean by design

Comms are async, open, and concise, with just enough structure to keep teams aligned without slowing them down. Working sessions leave useful artefacts behind, and tight feedback loops keep things clear and current. See our lean comms article for more on this.

- Safety and challenge are part of the culture

Teams feel comfortable raising risks, pushing back, and sharing work before it’s fully formed — with peers and with leadership. Leadership are visible, accessible, and open to being challenged. Feedback flows up, down, and across. That’s what makes collaboration sustainable.

When this works, the organisation feels connected but not clogged up. People know what’s going on, and how to contribute, without needing to be in every room.

Product strategy

It’s a set of connected, deliberate choices — about where to play, how to win, and what you’re choosing not to do. It sits between vision and roadmap, and links product thinking with commercial reality. Done well, it becomes the reference point for every major decision a team makes.

This isn’t about creating the perfect slide deck. It’s about being intentional — and getting those intentions out in the open.

At Hyperact, we structure product strategy around five core components:

- Context – a clear-eyed view of where you are now

- Success – a motivating picture of where you're trying to go

- Decisions – the big, directional bets about where to focus and how you’ll compete

- Measures – how you’ll know if you’re making progress

- Plan – coherent action across product, ops, and go-to-market

Each one’s tight and usable — grounded in reality, not jargon.

Making the shift

If you're serious about shifting how your organisation builds products, it helps to start small, and start grounded.

But first, ask yourself: are the conditions right?

You’ll have a better shot if you’ve got:

- Leadership support — ideally a CEO or CPO/CTO who’s seen this movie before

- A core of strong practitioners — people who know what good looks like and want to make it happen

- Low organisational baggage — fewer years of sales-led thinking, less legacy tech or outsourcing friction

- Good technical foundations — CI/CD, strong engineering culture, observability, lightweight governance

- Real appetite for change — and the energy to see it through

If you don’t have many of these in place, that doesn’t mean it’s impossible. But it does mean being honest about the hill you’re about to climb.

Teresa Torres made this point recently: without the right support, trying to lead change from the middle is like pushing a boulder uphill, only to have it roll back and flatten you.

Still, if you’ve got the spark, here are three moves worth trying:

- Start with a clear-eyed view of where you are - not the org chart or the planning rituals — the real friction points. Where are things slow, noisy, or just not working? Don’t map the whole thing. Find the edges with headroom.

- Don’t do it alone - change led by a single voice rarely sticks. Find one or two allies and try a different way of working inside a single team. Build from there. A small win is a powerful signal.

- Bring the customer into the room - real stories. Real insight. Real pain. When the customer problem is clear and visceral, it can cut through noise and shift the posture of even the most change-resistant orgs.

Be bold, but be realistic. Timebox your effort. If, after a few months, you’ve made no progress and burned all your energy, it’s okay to stop. Or to pivot. Or to try somewhere else.

This work isn’t easy. But if the conditions are right — or you can create the conditions — it’s worth a shot.

Anti-patterns

Not every attempt to modernise your product operating model lands well. Some stall. Some backfire. And some quietly add more noise than value. Here are a few familiar pitfalls to watch out for:

Transformation for transformation’s sake

Rolling out a new operating model just to feel like progress is being made. Renaming teams, rebranding rituals, creating frameworks that sound slick but solve nothing. If you can’t clearly explain what problem you're solving — and why this is the best way to solve it — then it's probably not worth doing.

Just loading more work onto already slammed teams

New operating models often start with good intentions, but end up as more stuff on top of existing expectations: more decks, more stand-ups, more rituals, more metrics. If you're not actively removing friction and freeing up time, you're not transforming — you're layering.

Doing it in isolation from the rest of the organisation

You can’t reshape how product works without involving the rest of the org. That means commercial, support, ops, finance — all the bits that orbit the product team. Otherwise, you just create tension. A shiny new model that expects lean loops and fast decisions... sitting inside a company that still runs on steering committees and approvals.

Copying someone else’s model without context

It worked at Spotify. That doesn’t mean it’ll work for you. Borrow ideas, sure — but shape them to your culture, constraints, and stage. What looks like best practice elsewhere can quickly turn into theatre if it’s not rooted in your reality.

Treating it as a one-off project

Operating models aren’t a thing you “launch” and then walk away from. They need care, iteration, and honest feedback loops. Otherwise, you end up with a dusty Confluence page and teams quietly drifting back to what they were doing before.

In summary

A strong product operating model isn’t a framework to adopt or a transformation to roll out. It’s a set of deliberate, evolving choices about how your teams work — and how your organisation sets them up to succeed.

There’s no single right shape. But if you’re serious about building better products, faster, it’s worth being serious about how you build the environment around them.

Further reading

If you want to go deeper, these are some of the more thoughtful takes on product operating models — each with a slightly different lens:

- Inspired, Empowered, and Transformed by Marty Cagan — along with SVPG’s introduction to the product operating model — offer a clear, structured take on modern product organisations. A solid foundation if you’re moving away from project-based delivery.

- Dotwork’s Product Operating Model starter pack by John Cutler – a comprehensive reference for teams that want to go deeper. It covers team scopes, artifacts, funding models, and interaction patterns in far more detail. Best suited if you need to design or refine the system layer.

- Itamar Gilad’s operating model for product-led organisations – a systems-level view that breaks organisations into eight interconnected functions, each with clear levers for change. Practical for teams adapting an existing setup.

None of them will be a perfect fit. But they’re all useful reference points — especially if you’re trying to shape something that works in your own context.