Product topology: Defining products, platforms, and services

We often use 'product' as a catch-all for digital products, platforms, and services. So when we describe ourselves as a 'product transformation consultancy,' what we're really saying is: we can help you transform your digital products, services, and platforms (and organisation). But you'll probably agree, that's a bit of a mouthful.

While it's deliberate (in the sense that we apply product-thinking to products, platforms, and services) it also creates confusion, which isn’t helpful when trying to affect change in an organisation – particularly when adopting the Product Operating Model.

We regularly see organisations trapped in debates over these definitions, or worse, making critical structural decisions based on unclear distinctions.

Often, these problems manifest themselves as:

- Products that aren't actually products (they're projects in disguise)

- Product teams subservient to service ownership, stripped of empowerment

- Internal platforms neglected or treated as cost centres

- Boundaries drawn too narrow, creating constant coordination overhead

- Boundaries drawn too wide, overloading teams beyond their cognitive capacity

- Products designed in isolation, devoid of service context

While it's important to start with clear definitions, the definitions themselves are only half the battle.

This article sets out how we characterise products, platforms, and services, how to draw boundaries between them, and makes the case for treating each of them ‘as-a-product’.

Services

We're going to start with services, as these sit at the top of the product topology.

A (digital) service is software responsible for helping end-users achieve one specific, high-level outcome, typically through a linear user journey. For example: learning to drive, applying for a mortgage, or switching energy suppliers.

Service boundaries are defined by what the user is trying to accomplish, not by what the organisation builds. 'Open a bank account' is a service. 'Account Management' is not – that's a product or platform that enables the service. Services are verbs, not nouns. This distinction shifts the frame of reference: where products and platforms are organisational constructs (ways of carving up ownership and capability), services are user constructs – the lens through which users experience what you've built.

You'll find services most commonly in service-oriented organisations like the public sector, or in organisations with complex product portfolios looking to optimise high-friction, infrequent transactions, such as financial services and utilities.

Services can be internal or external. External services help customers or citizens achieve an outcome like applying for a mortgage or learning to drive. Internal services help employees achieve an outcome. E.g. Onboarding a new starter, submitting expenses, or requesting IT equipment.

Services tend to be composed of multiple products and platforms. For example, an 'Apply for a mortgage' service might touch the banking app (product), identity verification (product), credit checking (platform), and document management (platform). The service is the thread that connects them, and can be viewed as an orchestration layer sitting above individual products and platforms.

Ownership is typically less clear than with products or platforms. It can be shared or, at worst, ambiguous or non-existent. This is a feature of how services work – they cross boundaries – but it's also a source of problems when nobody owns the end-to-end experience.

Services can be nested. A digital 'Learn to drive' service might encompass 'Apply for provisional licence,' 'Book theory test,' and 'Book practical test.' The outer service is the full user journey and the inner services are discrete steps with their own completion states. They're all services because they're all framed around user outcomes.

They also frequently incorporate non-digital touchpoints and processes, as well as digital. Used car buying sites like Cazoo and cinch are services. They help people buy used cars. While their ecommerce product is the primary digital touchpoint, there are a myriad of teams, systems, and processes involved, from the company acquiring the vehicle to it being delivered to its new owner and beyond.

Key characteristics

- Oriented around one specific, high-level user outcome

- Boundaries defined by user goals, not organisational structure

- Typically linear, high-friction, infrequent journeys

- Composed of multiple products and platforms

- Ownership is often shared, distributed, or ambiguous

- Often include non-digital touchpoints and processes

Products

A (digital) product is software that delivers value to end-users through a defined interface. Users interact with it directly and would recognise it as a thing. If services are verbs, products are nouns. 'Banking App' is a product. 'Open a bank account' is not – that's a service the product enables.

Unlike services, which orient around a single user outcome, products typically serve multiple, lower-level user goals through more frequent, routine interactions. Someone opens their banking app to check their balance, make a payment, or report a lost card. Different goals, same product. They can also be internal or external – their end-users might be within the organisation (like an intranet or internal tooling) or external (like a SaaS provider offering accounting software to small business owners).

Product boundaries are typically shaped by what the organisation can coherently own and maintain – but that doesn't mean those boundaries are necessarily optimal. Effective boundaries are informed by users' mental models and natural domain boundaries. Because of this, products typically have clearer ownership than services.

Products can be nested. A news app like the BBC or Guardian is a product. Within it, the Puzzles section might be considered its own product, owned by a distinct team with its own strategy, roadmap, and even its own revenue model (subscriptions, in the case of NYT Games). Products might also encompass everything a user touches (like a banking app) or a coherent subset of their experience (like Card Management).

A single product might also contribute to multiple services – the banking app plays a role in 'Open an account,' 'Apply for a mortgage,' and 'Report fraud.' Where services exist in an organisation, they sit at the top of the topology, products sit beneath them, and platforms – serving both. The main distinction between a product and a platform isn't scope; it's whether the owning team controls the user experience. If your team provides APIs that another team uses to build their screens and flows, it’s a platform, not a product.

Key characteristics

- Delivers value to end-users through a defined interface

- Serves multiple user goals through routine interactions

- Can be internal or external

- Boundaries shaped by what the organisation can coherently own

- Clear ownership

- Can be nested following domain boundaries

Platforms

The primary purpose of platforms is to reduce cognitive load on the teams that consume them. Rather than every product team figuring out identity, payments, or infrastructure from scratch, a platform encapsulates that complexity and exposes it through well-designed APIs, tools, and documentation. A good platform makes the right thing the easiest thing to do.

Where products are nouns that users recognise, platforms are the infrastructure beneath them. If your team provides APIs, components, or services that another team uses to build their user experience, you're running a platform.

Platforms are typically internal – serving teams within your organisation. A design system, an identity service, a data platform. When a capability is productised for external developers with a designed interface and developer experience, it becomes a product whose users happen to be developers. Stripe isn't a platform; it's a product for developers.

Platform boundaries are shaped by technical capability and domain, not user journeys. A platform typically encapsulates a coherent technical capability (e.g. payments, identity, notifications, search) that multiple products or services need. This is where Domain-Driven Design's concept of bounded contexts becomes particularly useful: a well-defined platform has clear interfaces and doesn't leak its internal complexity to consumers.

Platforms sit beneath products and services in the topology. An 'Apply for a mortgage' service might depend on a credit checking platform. A banking app (product) might depend on a payments platform. The platform doesn't own the user experience; it enables the teams that do.

Like products and services, platforms can be nested. A large organisation might have a data platform that contains sub-platforms: a data warehouse, a streaming platform, an analytics platform. Each can be owned by a distinct team with its own roadmap. Platforms can also have products built on top – a platform team might own both the APIs (the platform) and a developer portal (a product whose users are developers).

Key characteristics

- Provides capabilities consumed by other teams, not end-users directly

- Primary purpose is reducing cognitive load on consuming teams

- Boundaries shaped by technical capability and domain

- Clear, single-team ownership

- Can be nested following technical domain boundaries

- May have products built on top (e.g., developer portals, admin consoles)

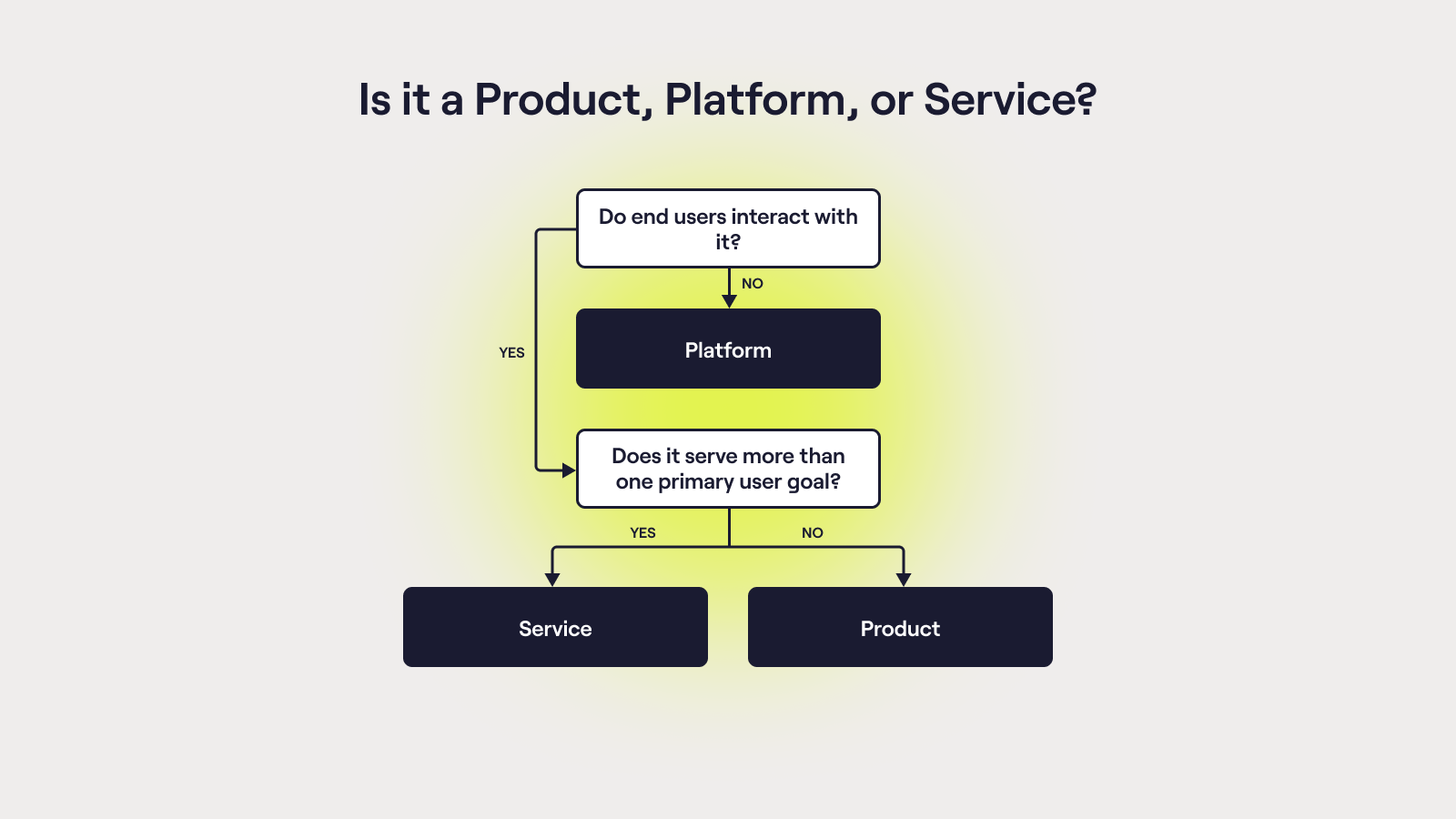

Or, if you need a short-hand:

Everything ‘as-a-product’

The previous sections define what products, platforms, and services are. This section is about how to manage them well.

Treating something 'as-a-product' means applying product management discipline to it – whether it's technically a product, platform, or service – and treating it with the same rigour you'd apply to customer-facing products.

Why does this matter? Because platforms and services often lack the intentional management that products receive. Platforms get treated as shared infrastructure – cost centres to be minimised rather than capabilities to be invested in. Services get fragmented across teams, with nobody accountable for the end-to-end experience.

Clear, empowered ownership

Every product, platform, and service needs clear ownership – a person or team accountable for its success. For products, this is usually obvious. For platforms and services, it's often missing.

Platform ownership frequently defaults to 'shared' or 'the infrastructure team,' which in practice means nobody is accountable for the developer experience, adoption, or evolution. Service ownership is often even worse – because services cross product boundaries, they often have no owner at all, or ownership is distributed across multiple teams who each optimise their slice while the overall journey suffers.

Empowerment is also critical. In service-oriented organisations, there's a risk that service owners become de facto product managers – dictating features to product teams who become delivery functions rather than empowered problem-solvers. This strips product teams of the autonomy they need to discover good solutions.

Clear ownership doesn't mean one person does everything. It means one person or team is accountable for outcomes, even when delivery involves others.

Close proximity to users

Products have users – this is obvious. But platforms and services have users too, and treating them as such changes how you manage them.

For platforms, your users are the teams that consume your APIs and tools. For services, your users are the people trying to achieve an outcome – but because services span multiple products, it's easy to lose sight of them.

Proximity means more than knowing who your users are. It means understanding their needs, building empathy for their problems, and actively involving them in discovery. The best teams maintain regular, direct contact with the people they serve – not mediated through layers of research reports or stakeholder proxies.

Measurable outcomes

"What gets measured gets improved" – Peter Drucker.

For products, this typically means end-user metrics: acquisition, activation, retention, engagement, satisfaction, task completion. For platforms, it means measuring the success of the teams you enable: Are they shipping faster? Are they adopting your platform voluntarily? Are they satisfied with the developer experience? For services, it means measuring the end-to-end outcome: Are users achieving their goal? Where are they dropping off? How long does the journey take?

The mistake is measuring activity rather than outcomes. Platforms that measure 'number of API calls' rather than 'time for a new team to onboard' are optimising for the wrong thing. Services that measure 'transactions processed' rather than 'users who successfully completed their goal' are missing the point.

Long-lived, cross-functional teams

Products benefit from continuity – teams that understand the domain, the users, and the codebase. The same applies to platforms and services.

This is where project thinking does the most damage. Projects assemble teams, deliver something, then disband. The 'product' enters maintenance mode. Knowledge walks out the door. There's no investment in improvement, no iteration based on what users actually need.

Product thinking assumes the work is never 'done.' Teams are long-lived. Funding is continuous. Success is measured by outcomes over time, not delivery against a specification. If your 'product' has a delivery date after which the team moves on, you're running a project – and you'll get project outcomes, not product outcomes.

Those teams should also be cross-functional – combining product, design, and engineering (and other skills as needed) in a single team with shared accountability. Cross-functional teams can move faster, make better decisions, and own problems end-to-end without constant handoffs and dependencies.

Strategic focus

Without a clearly defined, evidence-based strategy, teams struggle to fight against top-down, reactive decision making and lack valuable market context.

For products and services, strategy connects user needs, organisation goals, and competitive positioning. For platforms, the users are internal teams, the market is your internal ecosystem, and the competitive landscape might be build-vs-buy.

Whether it’s a broader portfolio strategy your product, platform, or service is aligning to, or whether it has its own, the strategy should define a long term vision, a framework for making reinforcing decisions, and a coherent set of actions – usually in the form of a roadmap – for achieving it.

Room to iterate and improve

Product teams don't just build – they discover, ship, learn, and improve. Platform and service teams should too.

This requires space for both continuous discovery and continuous delivery. Discovery means regularly testing assumptions, validating ideas with users, and learning what works before committing to build. Delivery means shipping, measuring, and refining based on what you learn.

Platforms often fall into a 'build and maintain' mindset – the platform exists, teams use it, and the platform team's job is to keep it running. This misses the opportunity to improve developer experience, simplify interface, and evolve with changing needs.

Services suffer from a similar problem. Once the journey is 'working,' attention shifts elsewhere. But user needs change, friction points emerge, and competitors improve. Services need ongoing investment, not just maintenance.

Summary

Products, platforms, and services have distinct characteristics – but all benefit from being treated ‘as-a-product’.

Services are oriented around user outcomes. Products are organised around what the organisation can coherently own and maintain. Platforms enable product and service teams to move fast without reinventing solutions to common problems.

Understanding these distinctions gives you a shared vocabulary. But what separates successful products, platforms, and services from neglected infrastructure and doomed projects is how they're designed and managed:

- Clear, empowered ownership

- Close proximity to end-users

- Measurable outcomes

- Long-lived, cross-functional teams

- Strategic focus

- Room to iterate and improve

So, as we said at the start: everything is a product.